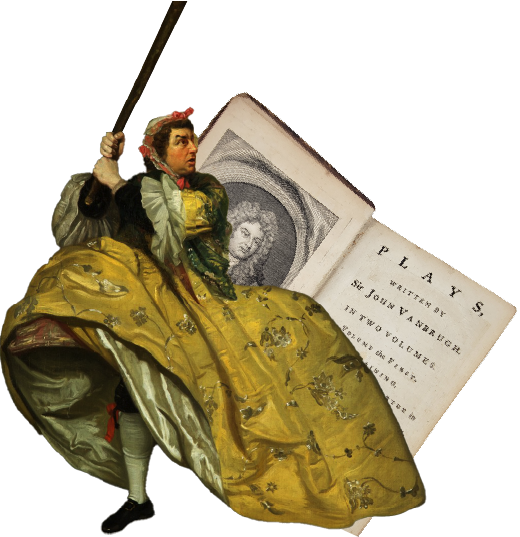

Gilbert Lovegrove, The Life, Work, and Influence of Sir John Vanbrugh (London, 1902).

Christian Barman, Sir John Vanbrugh (London: Ernest Benn, 1924)

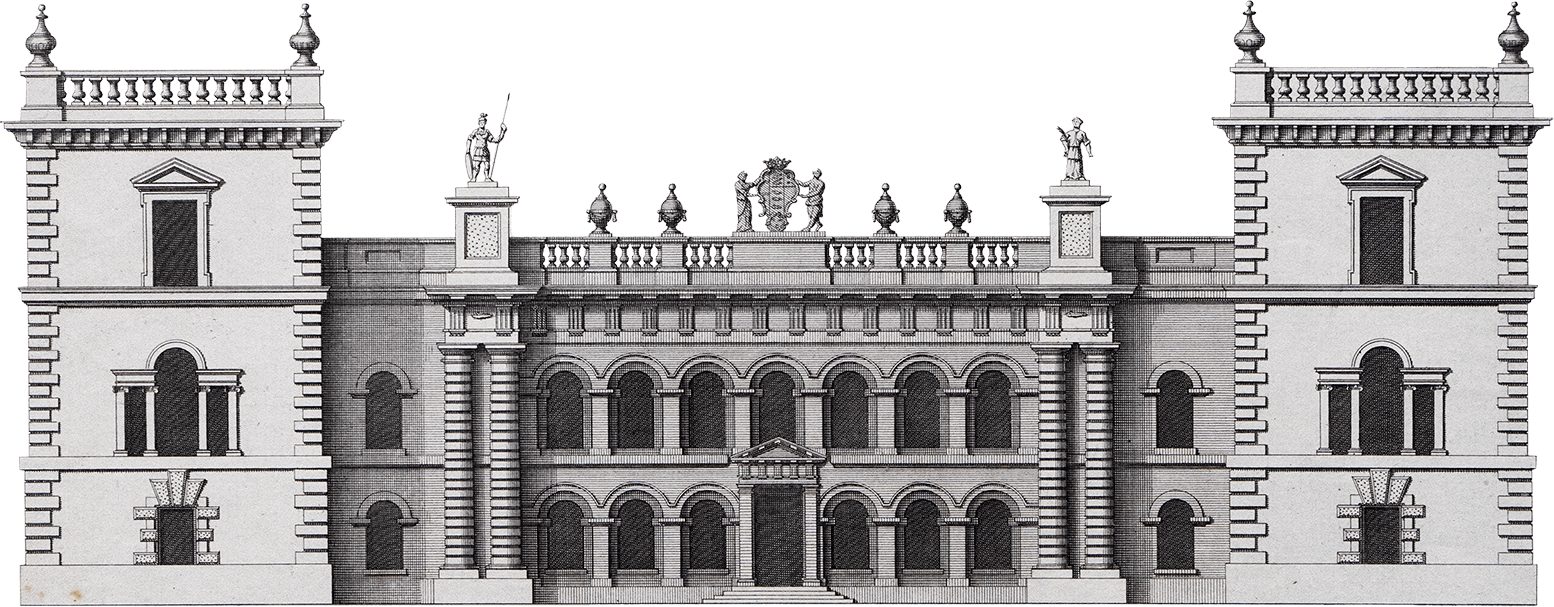

H. Avray Tipping and Christopher Hussey, The Work of John Vanbrugh and School 1699– 1736 (London: Country Life, 1928)

Geoffrey Webb, Vanbrugh’s Complete Works (London: Nonesuch Press, 1928)

Laurence Whistler, Sir John Vanbrugh: Architect & Dramatist 1664–1726 (London: Cobden-Sanderson, 1938)

Laurence Whistler, The Imagination of Vanbrugh and His Fellow Artists (London: Art and Technics, 1954)

David Green, Blenheim Palace (London: Country Life, 1951)

Kerry Downes, Sir John Vanbrugh: A Biography (London: Sidgwick & Jackson, 1987),

Kerry Downes, ‘Vanbrugh over Fifty Years’ in Christopher Ridgway and Robert Williams (eds.), Sir John Vanbrugh and Landscape Architecture in Baroque England 1690–1730 (Stroud: Sutton Publishing, 2000),

Geoffrey Beard, The Work of John Vanbrugh (London: B.T. Batsford, 1986)

Giles Worsley, In Search of the English Baroque: English Architecture in a European Context 1660–1725 with a chapter on ‘Vanbrugh and the Search for an English Architecture’ based on ‘Sir John Vanbrugh and the Search for a National Style’ in Michael Hall (ed.), Gothic Architecture and its Meanings 1550–1830 (Reading: Spire Books, 2002)

Vaughan Hart, Sir John Vanbrugh: Storyteller in Stone (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008),

Jeremy Musson, The Country Houses of Sir John Vanbrugh (London: Aurum, 2008)

Gavin Stamp, ‘Shakespeare in Stone’, first published in Apollo, January 2009 and republished in Anti-Ugly: Excursions in English Architecture and Design (London: Aurum, 2013)

Anthony Geraghty, ‘Castle Howard and the Interpretation of English Baroque Architecture’ in M. Hallett et al. (eds.), Court, Country, City: Essays on British Art and Architecture, 1660– 1735, Studies in British Art, 24 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016), pp 127–149.

Anthony Geraghty, Wren, Vanbrugh, Hawksmoor: Three Baroque Architects, Three Baroque Buildings (forthcoming)

James Legard, 'Queen Anne, Court Culture and the Construction of Blenheim Palace’ (Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies, 37:2, 2014, pp 185-197)